Peter III of Russia

Peter III of Russia was Emperor of Russia for six months in 1762. Circumstances of his death brought the possibility that Peter had not died but his wife Catherine imprisoned him. After his death, five people came forth and claimed to be the real heirs of the Russian throne.

False tsar Stephen the Little

In Montenegro, the Russian royal family was held in the highest reverence. That allowed a local commoner to ascend to the throne by presenting himself as Peter III, who escaped captivity. He even managed to unite the famously divided Montenegrin people and rule as tsar Šćepan Mali for 6 years.

Bishop Sava Petrović-Njegoš conveyed to the people a Russian message that Šćepan was an ordinary crook. Nevertheless, the people believed the “tsar” rather than Bishop Sava. Following this event, Šćepan the Little put Bishop Sava under house arrest in Stanjevići monastery. He was feared and respected to a great extent. Even when he admitted to being an imposter, the Montenegrin people kept him as their emperor. Petar II Petrović-Njegoš described this story in the epic “False Tsar Stephen the Little”.

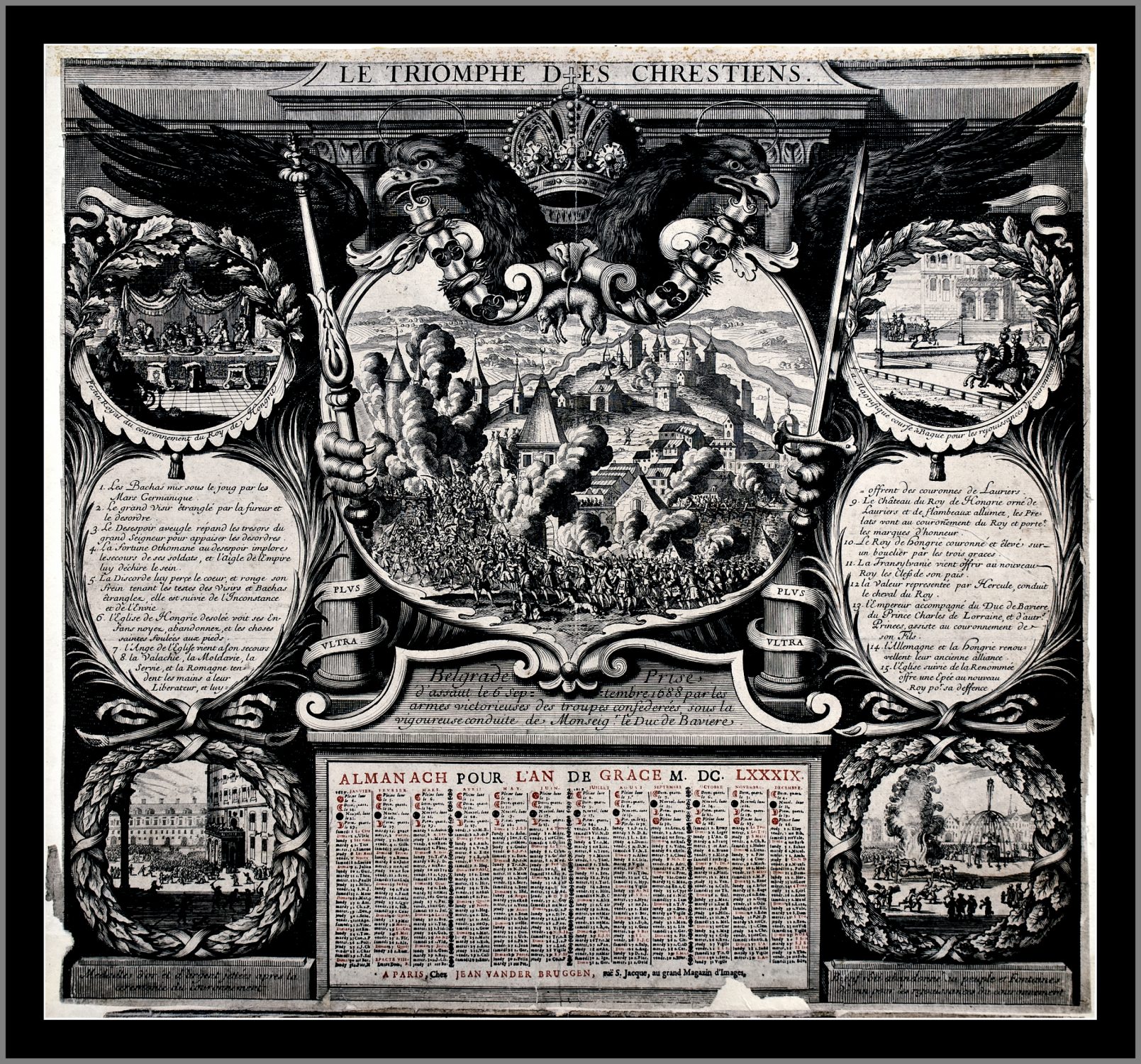

Yemelyan Pugachev – The false pretender

The most famous Peter III impersonator in Russia was Yemelyan Pugachev, a Cossack commoner. He led a popular insurrection against the rule of Catherine the Great, his supposed “wife”. A capable soldier, he was prone to impersonations and small criminal acts. After serving in the army in many campaigns for 7 years, he deserted to go home. Soon, he discovered the dissatisfaction of the Cossacks. Pretending to be Peter III, he led a successful revolt, capturing many important strategic locations. However, after a devastating defeat at the battle of Tsaritsyn, the Cossacks betrayed and surrendered him. The authorities publicly executed Pugachev in 1775 in Moscow. Alexander Pushkin presented A fictionalized account of the rebellion in the novella “The Captain’s Daughter”.

Kondratiy Ivanovich Selivanov

Another famous Peter impersonator was Kondratiy Ivanovich Selivanov. He pretended to be both Emperor Peter III and Jesus. He started a religious sect called Skoptsy, which preached a belief that access to Heaven was only possible through the castration of men and mastectomy of women. The belief was based on the original sin, which they interpreted as an instruction to distance themselves from sex. Despite imperial government prosecution, Skoptsy peaked in popularity in the early 20th century, with as many as 100,000 members. Alexandre Dumas wrote about the sect in his account of his journey through Caucasia, “Le Caucase, Memoires d’un Voyage”, 1858. Also In the book “The Idiot”, Fyodor Dostoevsky mentions Skoptsy tenants in a boarding house. Dostoevsky also mentions Skoptsy in the 1872 novel “Demons”.

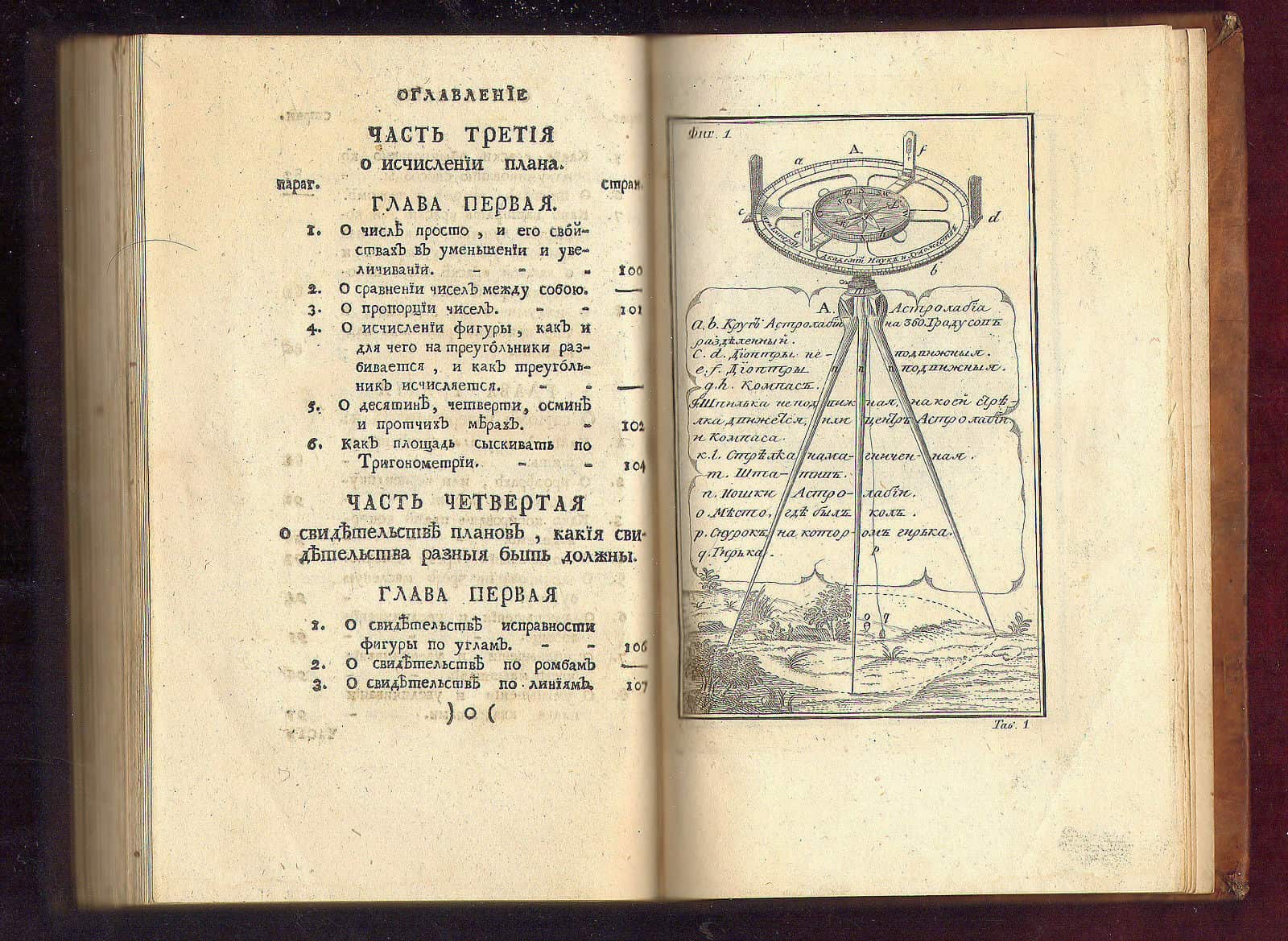

These were the most interesting impersonators of Petar III, the unfortunate Russian tsar. If you are interested in Russian history, feel free to browse through our collection of Russian books.