Translating the Scripture – Heresy or Populism?

Last time we talked about Orthodox books and now we will be talking about the Catholic side of Christianity. The question of translating the scripture sparked controversy throughout history. However, it also presented a crucial struggle for the democratization of the Catholic world. Today we will take a first look at the evolution of its language and history.

Bible and its Various Translations

Christian books were originally written in Hebrew, Greek and Latin. After the break of communion between what are now the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic Churches, many Orthodox Churches, like Russian, Greek, and Serbian, translated all their work into their own languages. Conversely, Catholics insisted that the only sacred were the three original languages.

Nevertheless, there hadn’t been a Bible originally written in Latin. The Old Testament was in Hebrew (with some parts in Greek and Aramaic) while the New Testament was in Greek. The Septuagint, still used in the Greek Orthodox Church, is a Jewish translation of the Old Testament into Koine Greek completed in the 1st century BC in Alexandria for Jews who spoke Greek as their first language.

The whole Christian Bible was therefore available in popular Greek by about 100 AD, but so were numerous apocryphal Gospels; deciding the Biblical canon by rejecting some of these took another two centuries or so, with some differences between churches remaining to the present day. In addition, the Septuagint included some books that weren’t a part of the accepted Hebrew Bible. The Vulgate is a late fourth-century Latin translation of the Bible that became, during the 16th century, the Catholic Church’s officially promulgated Latin version of the Bible. For most Christians in Western Europe, it was also the only version of the Bible they ever encountered.

Vulgata: The Vernacular Translation

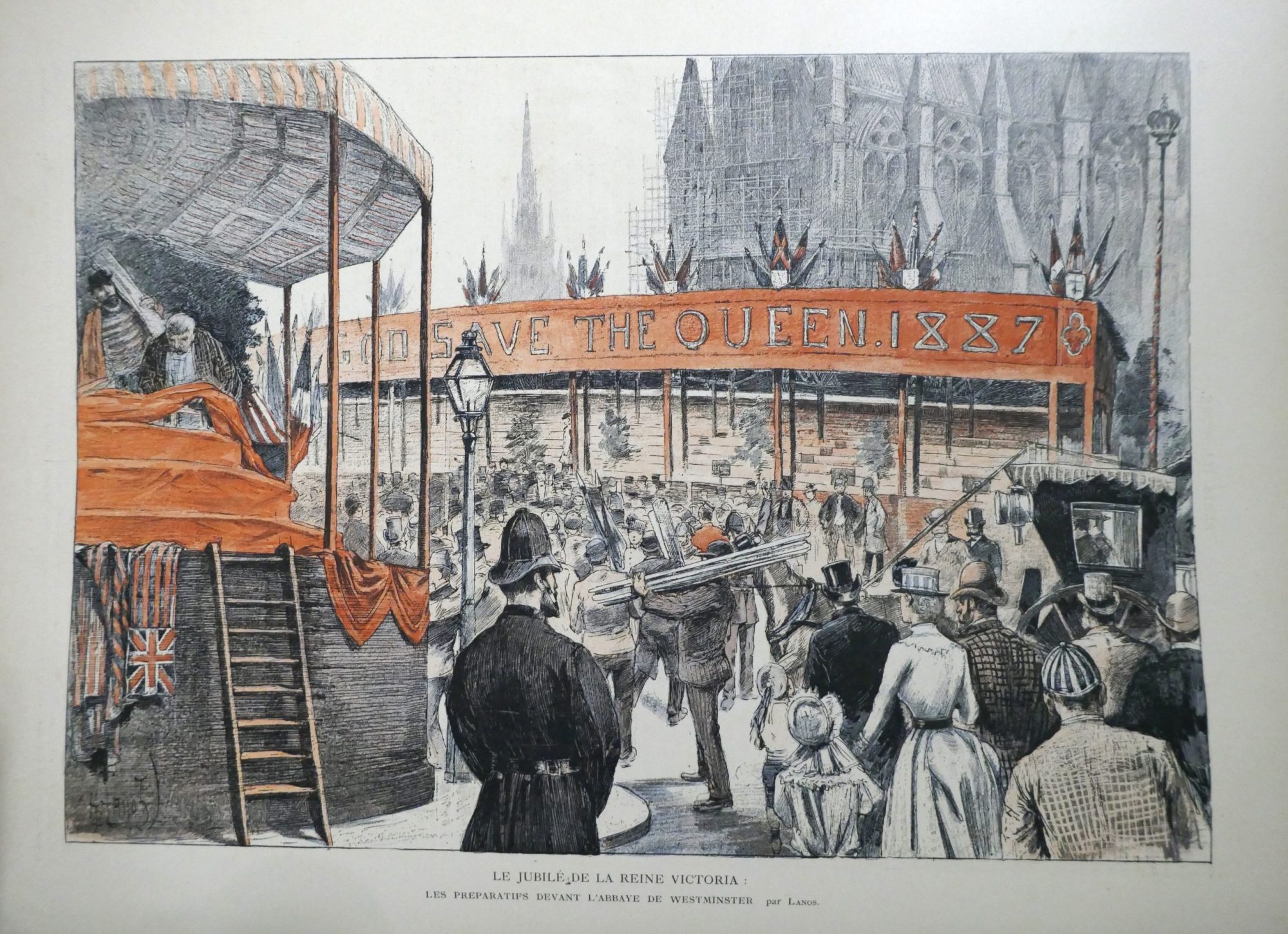

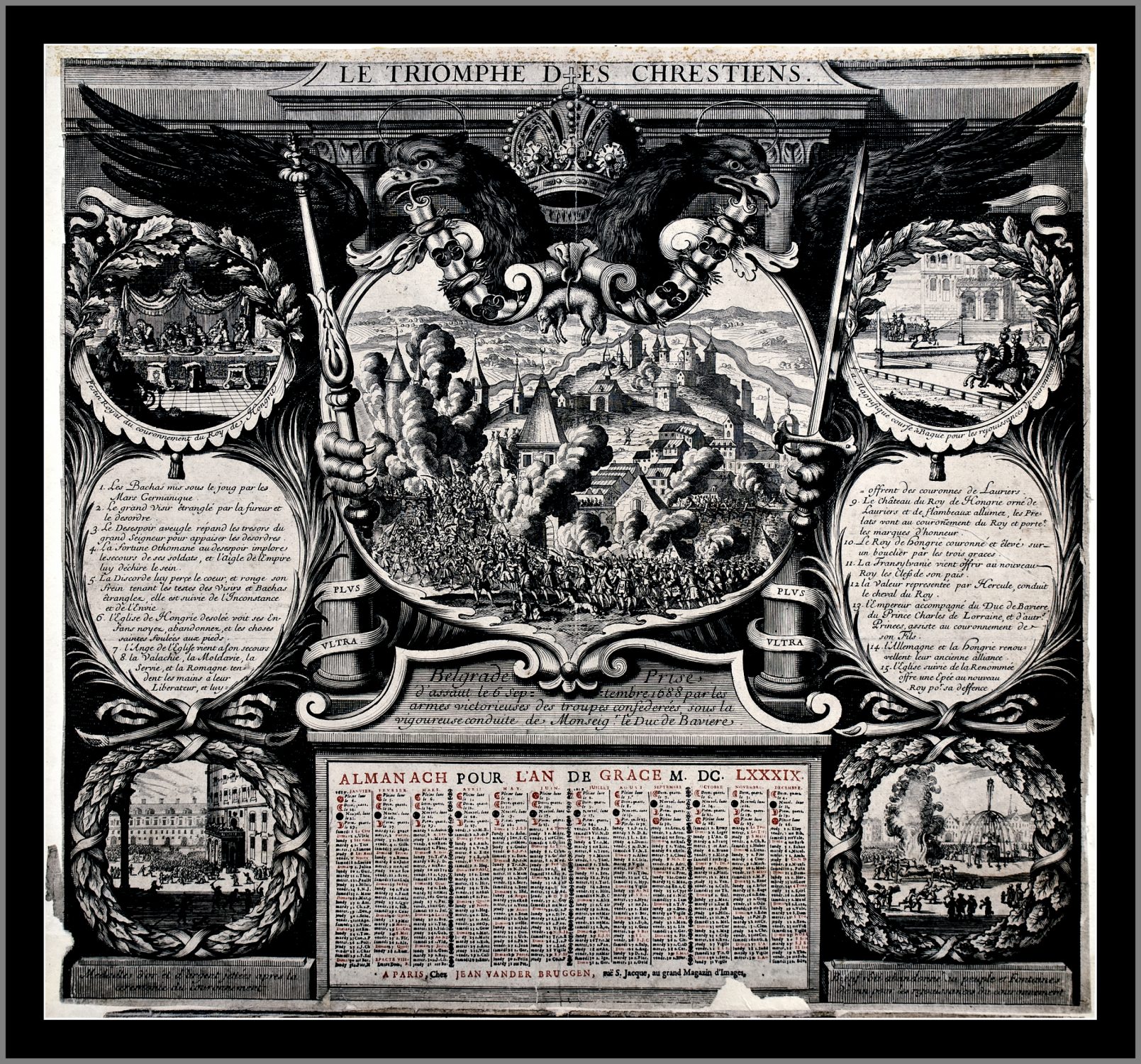

Aside from its use in prayer, liturgy, and private study, the Vulgate served as inspiration for ecclesiastical art and architecture, hymns, and countless paintings. A well-known group of letters from Pope Innocent III to the diocese of Metz is sometimes taken as evidence that Bible translations into vernacular were forbidden by the church, especially since Innocent’s first letter was later incorporated into canon law.

Another example is the ban of Wycliffite Bibles in England. The reason for the Catholic Church’s stance on translations into vernacular is the fear that those translations wouldn’t be accurate, would use vocabulary unacceptable to the church, and would also allow greater independence to those churches that did the translations. However, after Martin Luther translated the Bible to German, starting the Protestant Reformation, Roman Catholic Church realized the need to accept vernacular translations and put it onto itself to do it properly.

Protestant Reformation

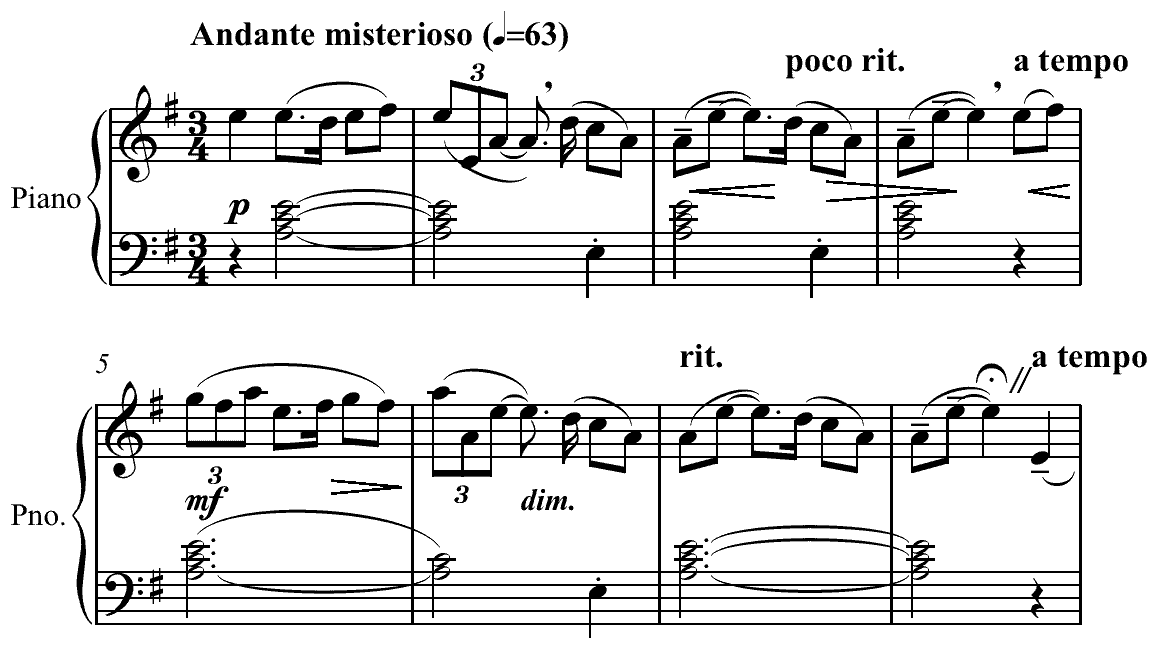

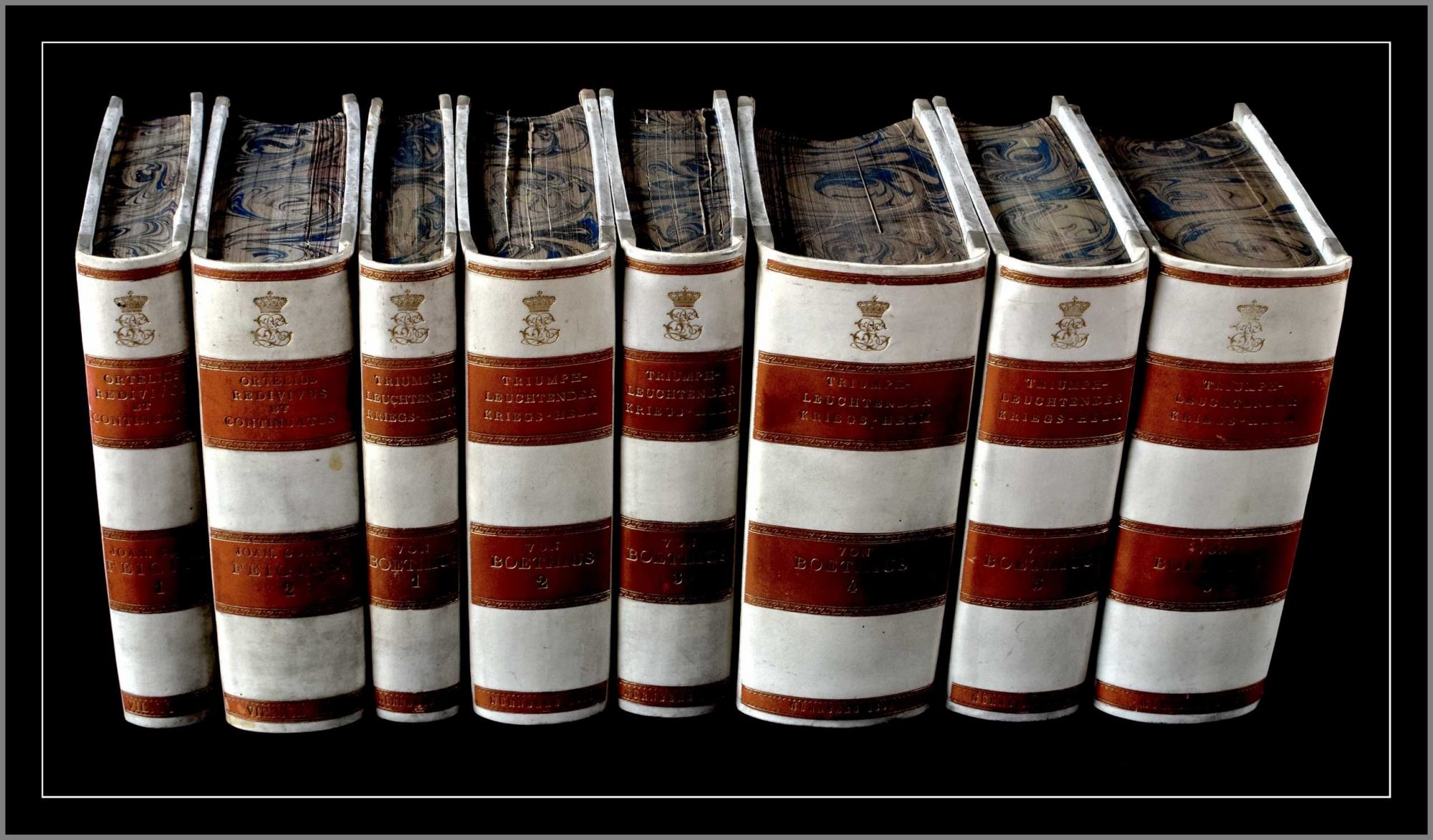

This is one of the earliest works to address that subject, printed only three decades after Martin Luther’s protestant reformation. It is noteworthy that a book about the Holy Scripture in Vulgar languages was also written in Latin:

De Vvlgari Sacrae Scriptvrae, Paris 1558. On the Holy Scripture in vulgar language.

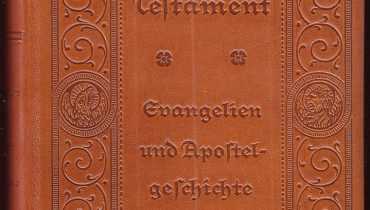

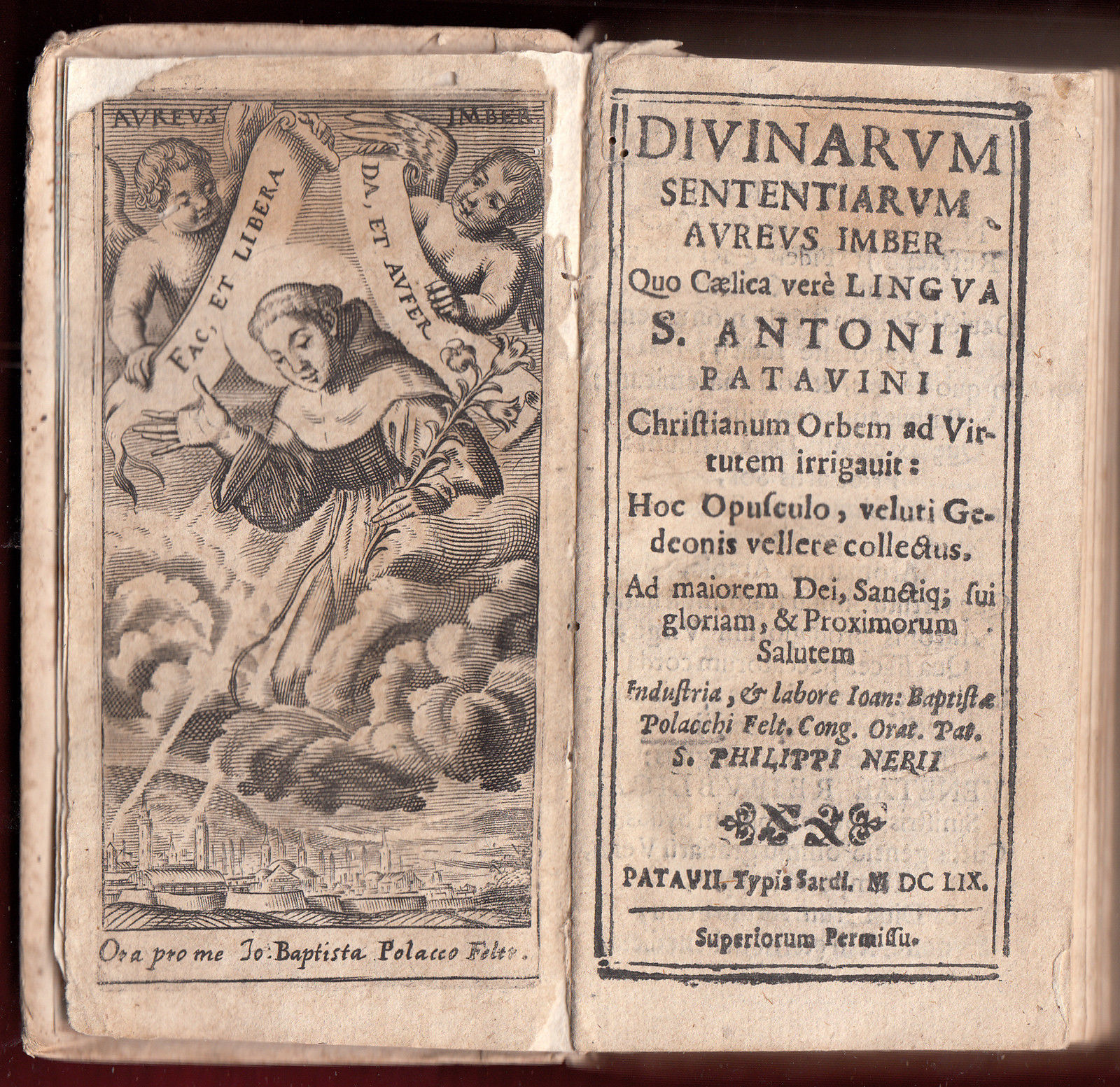

The other book is by Anthony of Padua, the second-most-quickly canonized saint, revered in his time for his knowledge of the scripture. He gained notice in his time for his eloquence as a public speaker, a preacher, and there is a story about his preaching beginnings. One day, in 1222, in the town of Forli, on the occasion of an ordination, a number of visiting friars were present, and there was some misunderstanding over who should preach. In this quandary, the head of the hermitage, who had no one among his own humble friars suitable for the occasion, called upon Anthony, whom he suspected was most qualified and entreated him to speak whatever the Holy Spirit should put into his mouth. Not only his rich voice and arresting manner, but the entire theme and substance of his discourse and his moving eloquence, held the attention of his hearers. Everyone was impressed with his knowledge of Scripture. His written word is now held in the highest of regards.

The divine words of Anthony of Padua (Antonii Patavani). Printed in Padua 1659.

Срђан Димитријевић

Srđan Dimitrijević

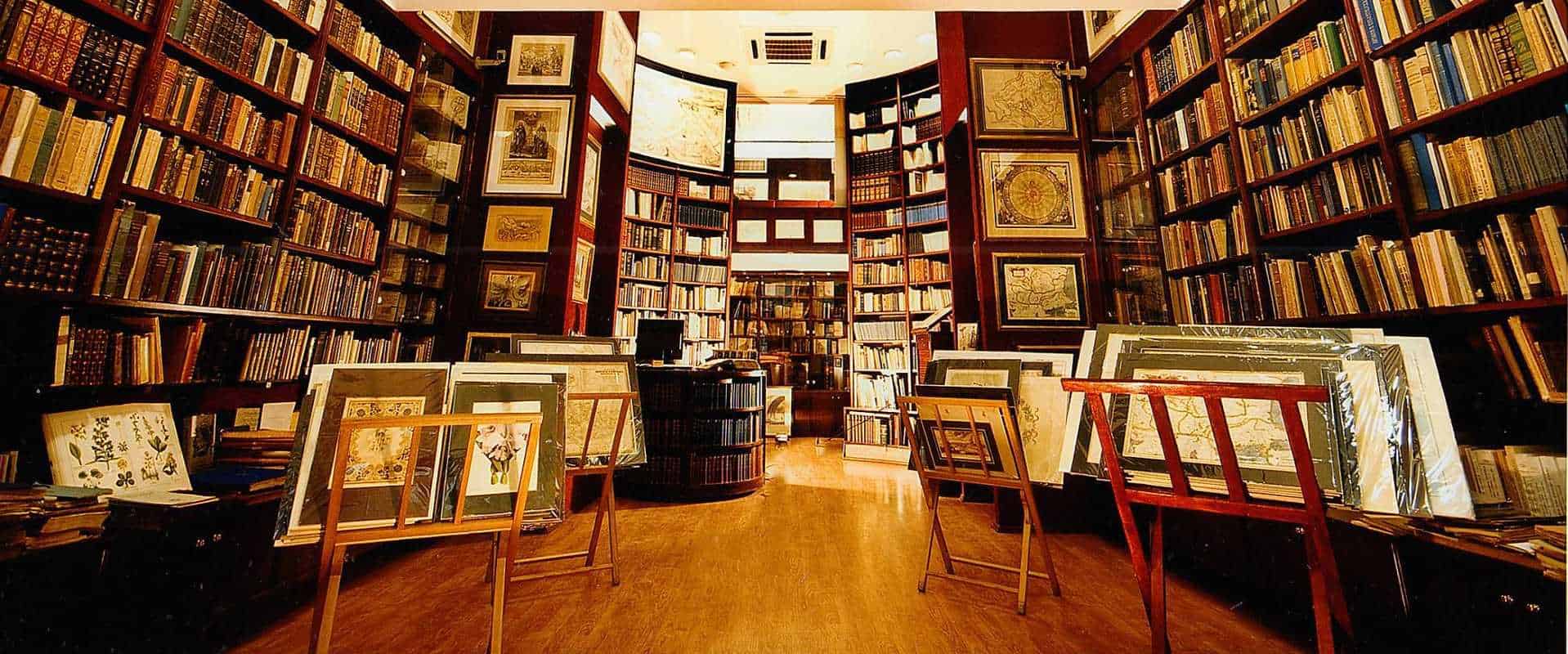

Book illustrations are taken from listings active on Sigedon Books and Antiques store on eBay.