Blog

Beginnings of printing in Serbia, the Struggle for culture

Beginnings of printing in Serbia: the Struggle for Culture

The major part of the history of printing in Serbia is actually the tale of the culture struggling with difficult historical circumstances. The beginnings of printing coincide with the beginnings of great Ottomans conquests.

Preserving Identity During Ottoman Colonialism

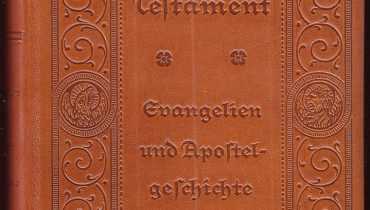

At the same time Gutenberg’s Bible appeared (1453), Sultan Mohamed the Conqueror took Constantinople, the Byzantine capital. By then, the Ottoman Empire conquered the whole of Serbia. Guttenberg himself was aware of the great danger that threatened the whole continent. Thus, in 1454, a year before publishing the Bible, he published the so-called Turkish Calendar, calling for resistance against the Ottomans.

By the year 1459, just four years after Gutenberg Bible finished printing, the of whole Serbia was occupied by Ottomans. These historical circumstances have greatly determined the nature of Serbian book printing.

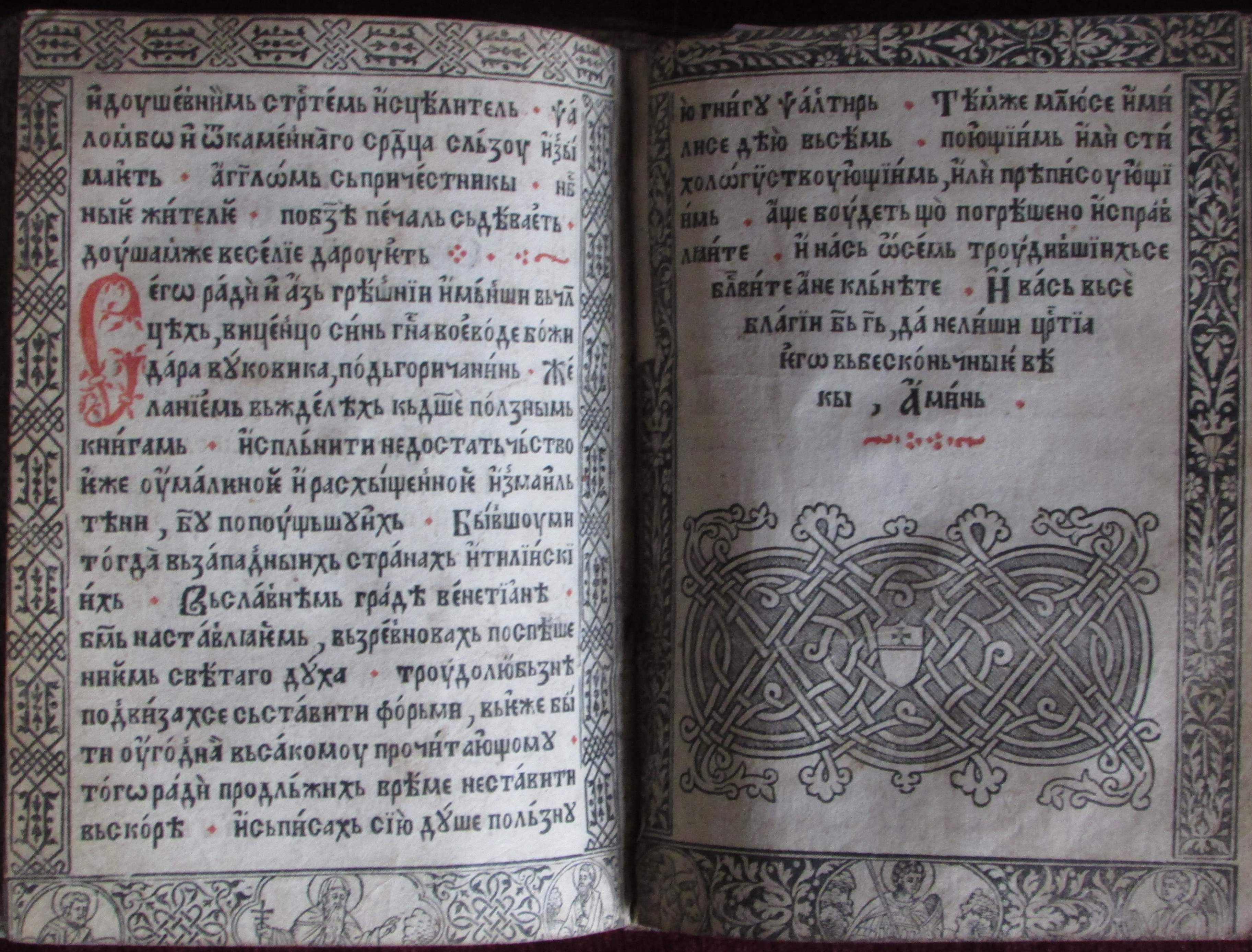

Псалтир са Послиатованием (Psaltir sa Posliatovaniem) printed in Venice, 1546 by Vincenco Vuković. Arguably one of the most beautifully decorated books of the 16th century. The margins around the black and red printed text are different for every page.

The primary goal of printing in Serbia was to preserve national, cultural, and spiritual self-consciousness. Only religious, orthodox books were printed in Serbia, as the main goal of the Serbian people was to resist Islamization and preserve the Serbian Orthodox faith. Sometimes these books contained some pieces of educative information. Led by a strong desire to preserve national and religious identity, the last medieval ruler of the country of Zeta (nowadays Montenegro), Ђурађ Црнојевић (Djurdje Crnojevic), commissioned the opening of the first Serbian printing house in Cetinje. His printers from Hieromonk Makarije onward managed to print five books in the period from 1494 to 1496.

First Printed Books

First of them was Oktoih Prvoglasnik (Ocotechos of First Tone), which also represents the first book printed in Cyrillic in Southeast Europe. It appeared on January 4th, 1494. This book contains hymns meant to be sung to the first four tones of the Octoechos System, a musical system of eight tones, which has Byzantine origin. The book is characterized by high-quality two-colored printing, red and black. Its decorations and initials remind a lot of the Renaissance style of decoration.

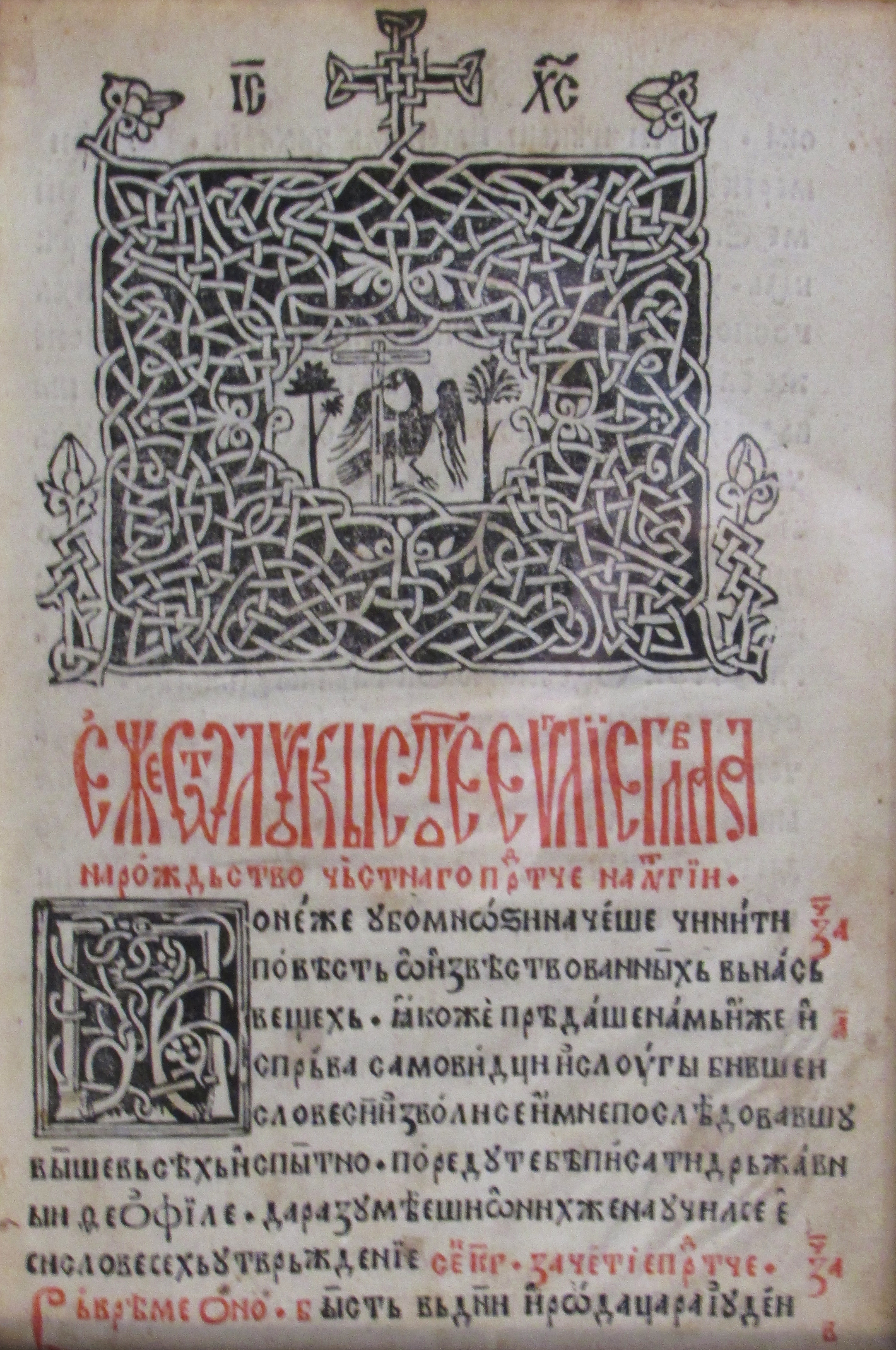

Leaf of the Београдско Четворојеванђеље (Beogradsko Četvorojevandjelje), the first book printed in Belgrade, 1552.

After the fall of Zeta and the destruction of Crnojevic’s printing house, the people of Serbia had to seek foreign cultural shelters and support. The mission of printing firstly continued in Romania. In the year 1507, Hieromonk Makarije started to print religious books in Bulgarian redaction, which was then used in Romania. These outstanding editions showed great similarity with books printed in Cetinje.

The Venetian Printing House

The main base of Serbian printing at that time, however, was Venice. Here, Божидар Вуковић (Bozidar Vukovic), born in Podgorica, Montenegro, continued to print Serbian religious books between 1520 and 1560. His son, Винћенцо Вуковић (Vicenzo Vukovic) continued the tradition of printing up until the very end of the 16th century. During the time of the Vukovic printing house in Venice, Serbia witnessed the printing of some significant books. During the first period of printing, this house printed the first Srbulje (Cyrillic books on Serboslavonic language, Serbian recension of Church Slavonic).

In the second period, this house also published several religious books (Psalter, Liturgijar, Molitvenik, and Zbornik). The most luxurious and lengthiest edition was Praznični Minej. Books that Bozidar Vukovic printed were so popular, that his son, upon inheriting the printing house up until 1561, made only reprints of his father’s books and sold them successfully. In 1561 Vicenco engaged Stefan Marinovic to operate the printing process. He printed Posni Triod and Jakov of Kamena Reka printed The Book of Hours (Часослов) in 1566. Books printed in Vuković’s printing house significantly influenced books printed in Russian, Greek, and particularly Romanian language.

From One Empire to the Next

Opportunities for printing Serbian books within the borders of the Ottoman Empire were very weak. The seventeenth century was a particularly dark period for Serbian printing and culture in general. Certain renaissance will come in the 18th century when Serbian book will find shelter within the borders of the Habsburg Monarchy.