Blog

18th century Serbian books – Struggle for independence

18th-Century Serbian Books – Struggle for Independence

After a dark and painful 17th century for Serbian culture and printing, the country experienced a renaissance in the 18th century. This was due to the book market expanding to the Habsburg Empire, where the majority of Serbian people had lived. However, local authorities didn’t allow the establishment of the Serbian printing house. They persistently refused repeated pleas of Serbian religious leaders to establish an independent printing house in the Habsburg Empire. The main reason was the belief that Serbs were more likely to accept union with Roman Catholic Church if they didn’t have published ecclesiastical writings.

Nevertheless, metropolitans of the Serbian church managed to print a number of important books in Russian redaction of Church Slavonic. These books were printed in the cities of Rymnik (Walachia) and Iasi (Moldavia). The second way of publishing was engraving editions published by authors and supported by the Serbian Orthodox Church. Examples of these editions were works by Hristifor Zefarović (Христифор Жефаровић) and later on, Zaharije Orfelin (Захарије Орфелин). However, this was not enough to provide steady development of Serbian culture.

The First Cyrillic Department

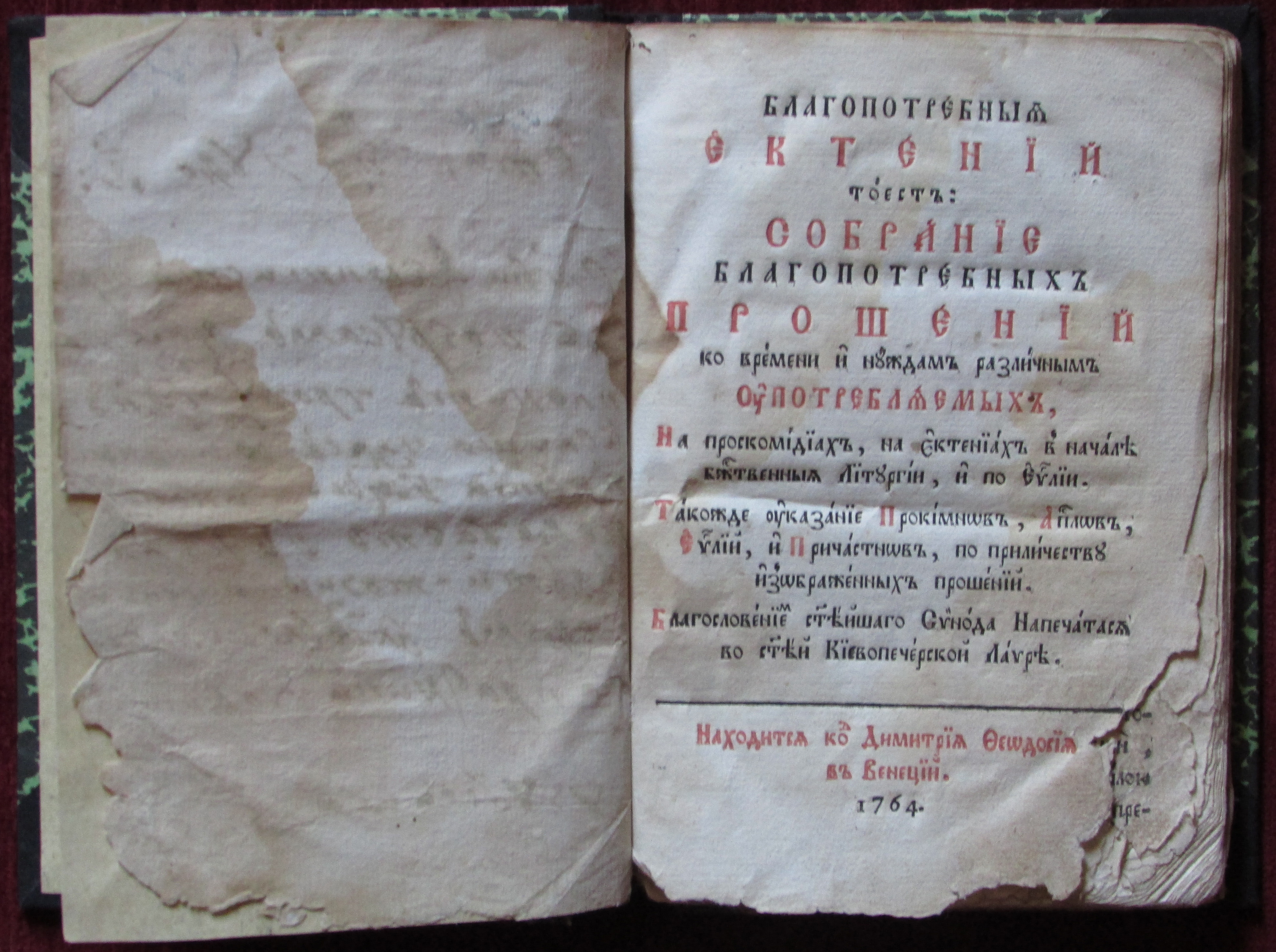

The publication of Serbian books gained momentum in 1761 when the Venetian printer Dimitrios Theodosios (Δημητριος Θεοδοσιος) opened a Cyrillic department in his printing house. While printing Serbian Orthodox books, he had to overcome the suspicion of the Serbian clergy toward the books coming from the Catholic milieu.

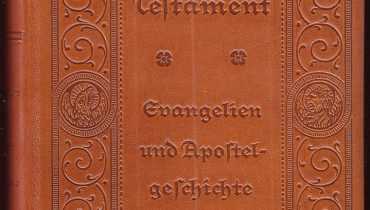

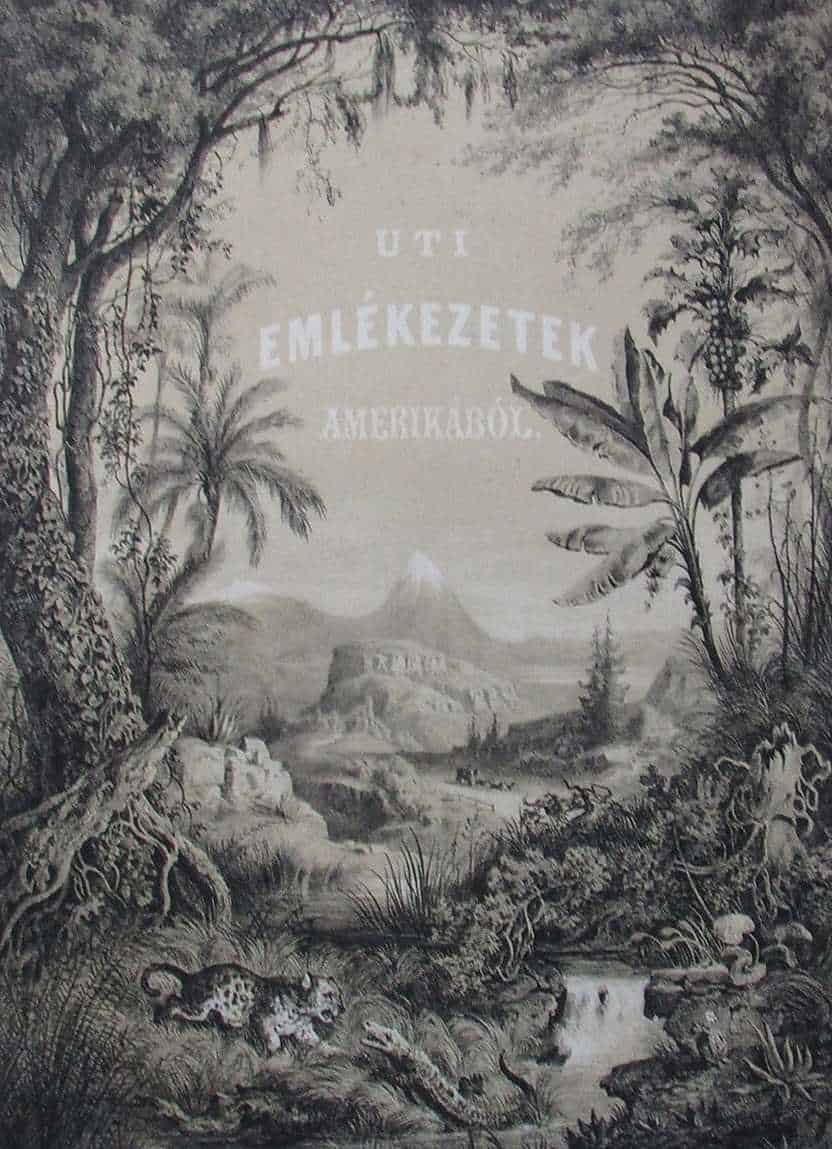

One of the books printed in printing house of Dimitrios Theodosios in Venice, for the needs of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

To avoid their distrust, he would indicate on the title page Moscow, Kiev, or Saint Petersburg as the place of printing. This was not true, but it wasn’t far from it either. Namely, Theodosios was doing reprints of Russian books for the needs of the Serbian Orthodox Church. This printing house in Venice took a large role in the publication of Serbian books. During ten years of work, this house published over forty books dedicated to the Serbian people.

Monopoly rights for printing Serbian books

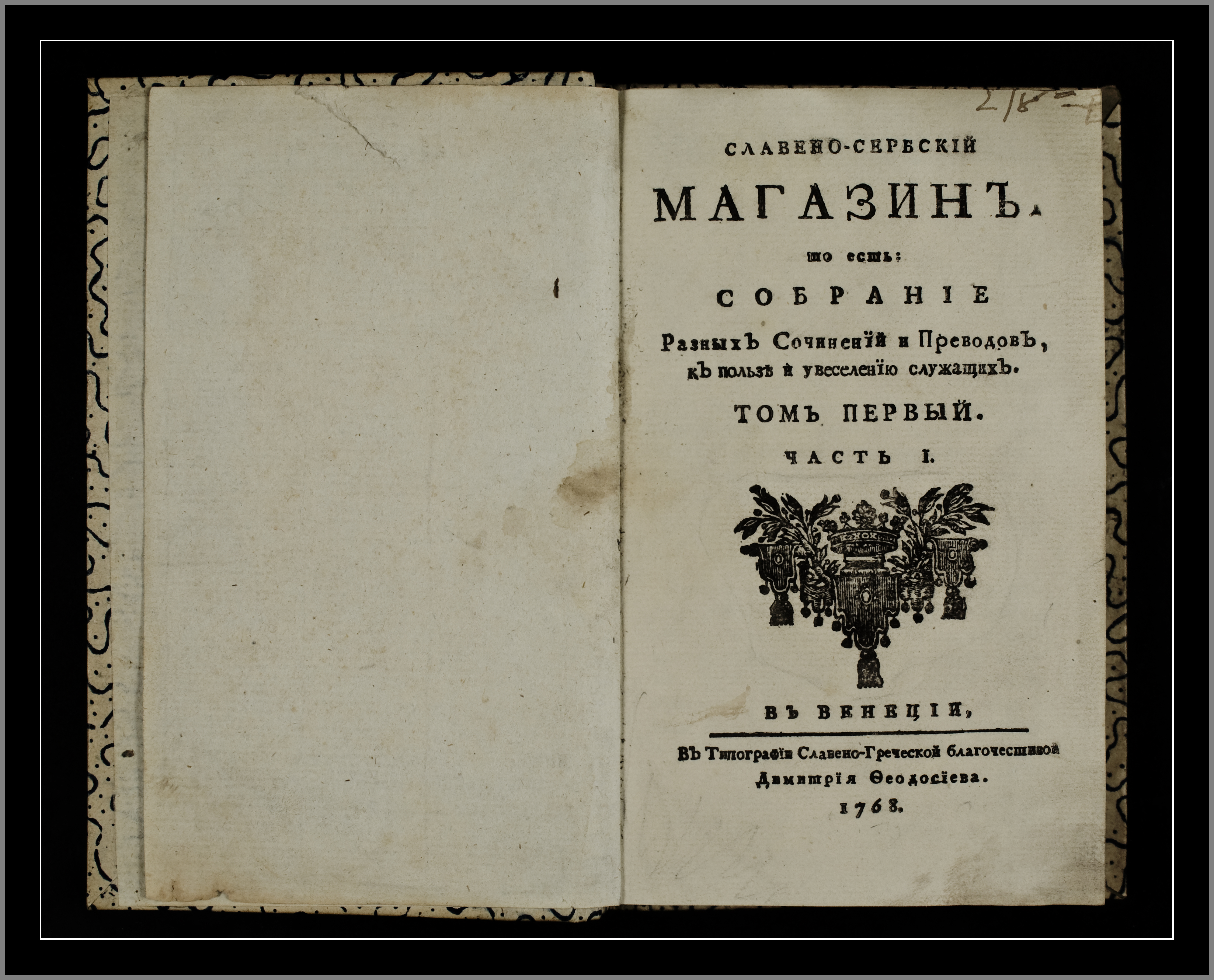

Soon enough Austrian authorities realized that forbidding the printing of Orthodox books is counterproductive. By doing so, they opened up the doors for a stronger Russian influence. With this came the financial loss from book sales to a foreign printing house. In 1770, a Viennese printer Jozef Kurzbeck (Joseph Kurzböck) received the monopoly rights for printing Serbian books. By giving such a privilege to a Viennese entrepreneur the Austrian government provided tight control of the Serbian literary production. Nevertheless, Dimitrios Theodosios managed to print several more books dedicated to the Serbian people. This included the fundamental History of Peter the Great (Историја Петра Первога), written by Zaharije Orfelin.

„Slaveno-serbskij magazin“ written in Slavonic-Serbian language. The first magazine in Serbian culture and the most significant work by Serbian educator Zaharije Orfelin.

The Struggle Continues

In 1790, Emanuel Janković (Емануел Јанковић) and Damjan Kaulić (Дамјан Каулић) separately filed the request for the establishment of a Serbian printing house in Novi Sad. Sadly, they were both rejected by the Viennese authorities. However, in 1792, after the death of Kurzbeck, a Serbian enthusiast and journalist Stefan Novaković (Стефан Новаковић) bought his Cyrillic printing press, together with its monopoly. Unfortunately, this proved a financial failure and eventually, Novaković was forced to sell the company. He sold the company to the printing house at Univerity of Pest.

This was a highly-developed company that printed books in many languages and which, for decades, held a monopoly on the printing of Serbian books in the Habsburg Monarchy. That was a huge blow to Serbian publishing. Only in rare cases, some Serbian authors managed to publish the book in Habsburg Monarchy or abroad. This was the case up until 1832 when in Belgrade, under the rule of Miloš Obrenović, the Serbian government opened Srpska knjaževska pečatnja. This is known today as Beogradski izdavačko-grafički zavod, or simply BIGZ.

Photos of the books shown above provided by private collections.