Blog

Frontisterion – Between Protest And Performance

Frontisterion – Between Protest And Performance

In the aftermath of the student protests of ’68 in Yugoslavia, a small group of three students decided to fight fear with laughter. Their satirical magazine Frontisterion didn’t live to see its first publication. It was seized and burned before left the printing house. What was so subversive about a student periodical that it had to be banned and burned?

Student Insurrection

The memorable 1968 was an especially turbulent year across the globe. Protests spread like wildfire among students and workers against the bureaucratic regimes. Along with half of Europe, the USA, Mexico City, and Brazil, Yugoslavia played its part in the protest. However, the June events were scarcely covered by the Western media and even less so analyzed in the aftermath. The idea of a socialist and liberal Yugoslavia clouded the seriousness of the events that took place.

It all started on the night of 2 June when the police expelled a group of students from a small theatre that featured a play only for the Youth-Action members. Revolted by this, students gathered and entered a conflict with the police, that would grow into a seven-day strike. Beatings and the following banning of all public gatherings pushed the students to seclude themselves in the amphitheater of the Faculty of Philosophy. There they held debates and speeches on social justice and handed out banned copies of the magazine Student.

The Aftermath

During a televised speech on 9 June, Josip Broz Tito declared that “the students are right”, intending thus to pacify the protests. Nevertheless, the state imprisoned students who led the protest and fired professors who supported them.

However, after the expulsion of old members of the League of Communists in the fall of ’69, the party government had a problem. They wanted to elect a new faculty committee at the Faculty of Philosophy. At the same time, they needed to ensure that all that were active during June ’68 were kept out. They were looking for a neutral, good, and obedient student to carry out the rigged elections. Little did they know that Svetlana Slapšak, who happened to be awarded as the best student of the faculty, was also one of the faces lost in the ’68 crowd.

Svetlana grabbed the opportunity “with both hands”, she says and conducted elections in a traditional fashion of Athenian democracy. The unassuming student of classical studies thus turned out to be a leading figure in the satirical revolt.

Frontisterion: performance of protest?

On the second anniversary of the June protests in 1970, Svetlana, along with Zoran Minderović and Milan Ćirković, launched the satirical students’ magazine Frontisterion. They were the chief – and only – editors, as other students didn’t want to associate themselves with the esoteric playfulness of their humor. Although playful, it wasn’t as innocent as it turned out.

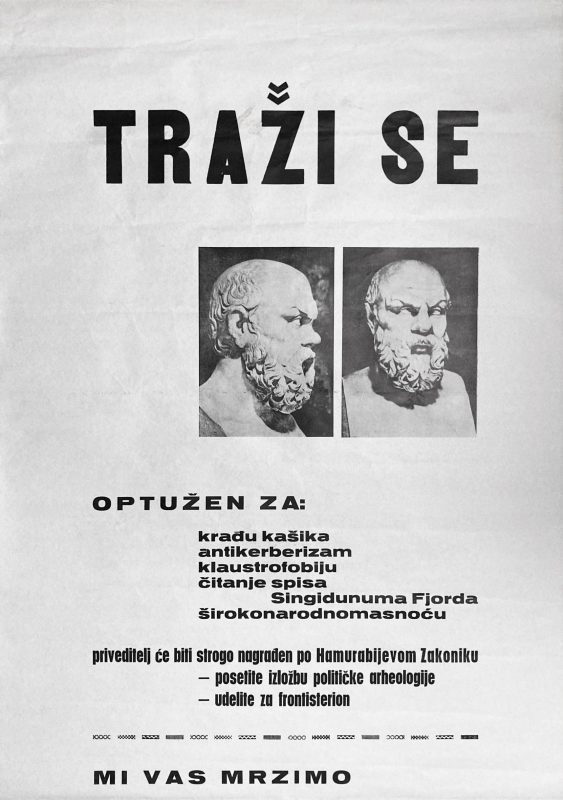

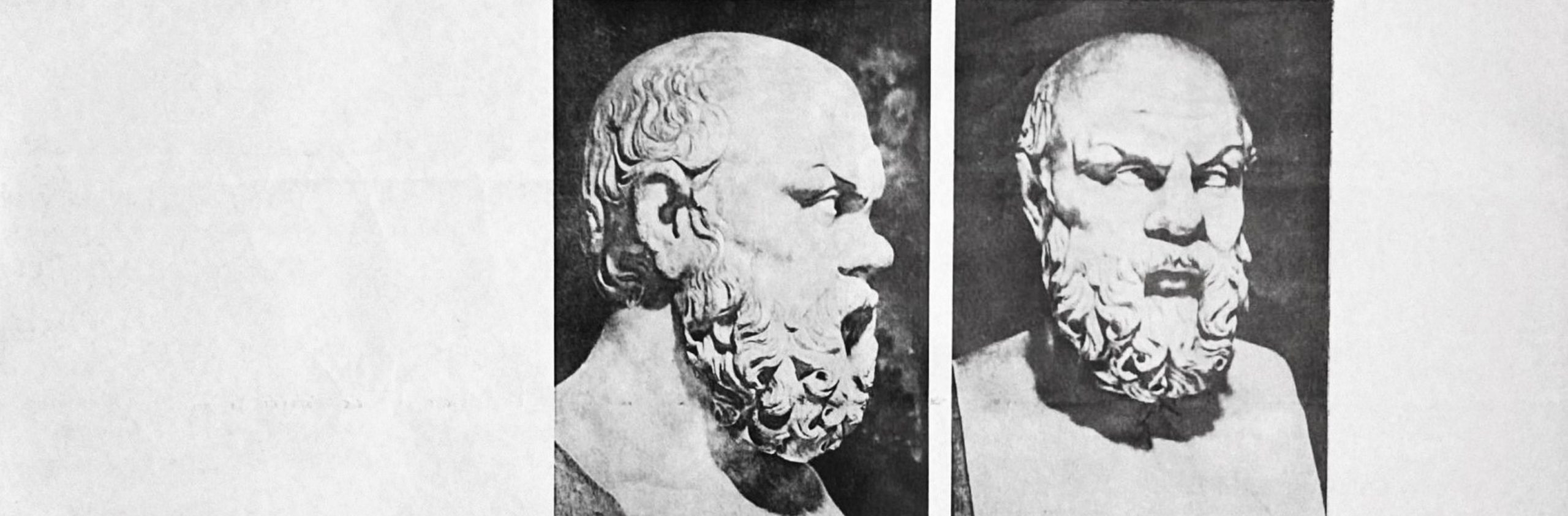

The name “Frontisterion” was borrowed from the play The Clouds by Aristophanes, a term designating the “thinking room” in which Socrates hangs from the ceiling and thinks. This was an homage to Aristophanes himself as well, whose brand of humor they, no doubt, inherited.

“We are the pride of our mother. We hate you. We stand on the stances of a critical twist on the entire hysteria of humanity.”

– Journal for students of the Faculty of Philosophy, Draining logos (excavation mark)

The three allied with the printing house Kosmos, which can still be found near Slavija Square. The magazine had great success with the audience at Kosmos. The students were happy to see that the workers at the printing house cracked their cyphered humor, hidden invectives, and quoted their jokes amongst themselves.

For the release of the magazine, the students prepared an exhibition on “Political Archeology” with the slogan “We hate you”. The poster was a mockup warrant, indicting Socrates of stealing spoons, anticerberism, claustrophobia, claustrophobia, reading the writings of Singidunum Fjord, and so on.

Despite the support from professors such as Nebojša Popov, both the event and the magazine were quietly suppressed. Frontisterion was seized before its official release and the three dissidents had to “smuggle” several copies out of the printing house before they were destroyed. Reflecting on these events, Slapšak admitted that they were a testament to the overall hysteria of the government, rather than the avant-garde humor itself.

Satire in Court

But the final price was paid by the president of the student board Vlada Mijanović, who ended up in prison. The rest of them were only to lose their passports and the possibility of a career. Of course, the trial awaited Vladimir, a.k.a. Vlada Revolution, long before, but now Slapšak too got involved. She was allegedly called as a witness in the trial and interviewed in the investigative procedure. It lasted about 8 hours, during which Svetlana gave a lecture in her field – on the etymology of ancient Greek words. She would convince them that “basileus” etymologically doesn’t mean king at all – which was a lie. This was a way to confuse the Investigative Judge and hide the true meaning of their provocative intertextual play.

“I used everything I knew from the etymology and historical phonetics of Greek, I think some of my arguments at that time would have passed the professional evaluation.”

Slapšak would later admit that this was “the most the most brilliant lecture” of her career.

Significance of Frontisterion

The magazine itself had virtually no effect on the public nor was it recognized by its peers. Slapšak, Minderović, and Ćirković went on to write their satirical essays and made tape recordings that circled Belgrade through the ether. Shortly after, this too stopped as the group disassembled.

Nevertheless, the effort of the three students was acknowledged by those such as Professor Nebojša Popov, who recognized the democratic roots of their humor. In some respect, in ancient Greece, comedy was far more important than tragedy in a political sense. In a comedy, you were allowed, at least for a brief period, to call out any citizen and make a fool of them. Frontisterion, Slapšak points out, was also a kind of inscription in such a ludic European tradition.

They all continued, in their way, to fight for these values for a long time. Slapšak is now an award-winning essayist and a 2005 candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize.