Blog

Unknown Influences of Jules Renouard

The Unknown Influences of Jules Renouard

We don’t know much about Jules Renouard, even though he was one of the most influential book dealers and editors in 19th-century Paris. The name Renouard gained recognition mostly due to his father, a political activist in Paris at the time of the French Revolution. Born nine years after the fall of the Bastille, Jules continued in his father’s footsteps to publish numerous editions of books and maps.

Booksellers Trade Union

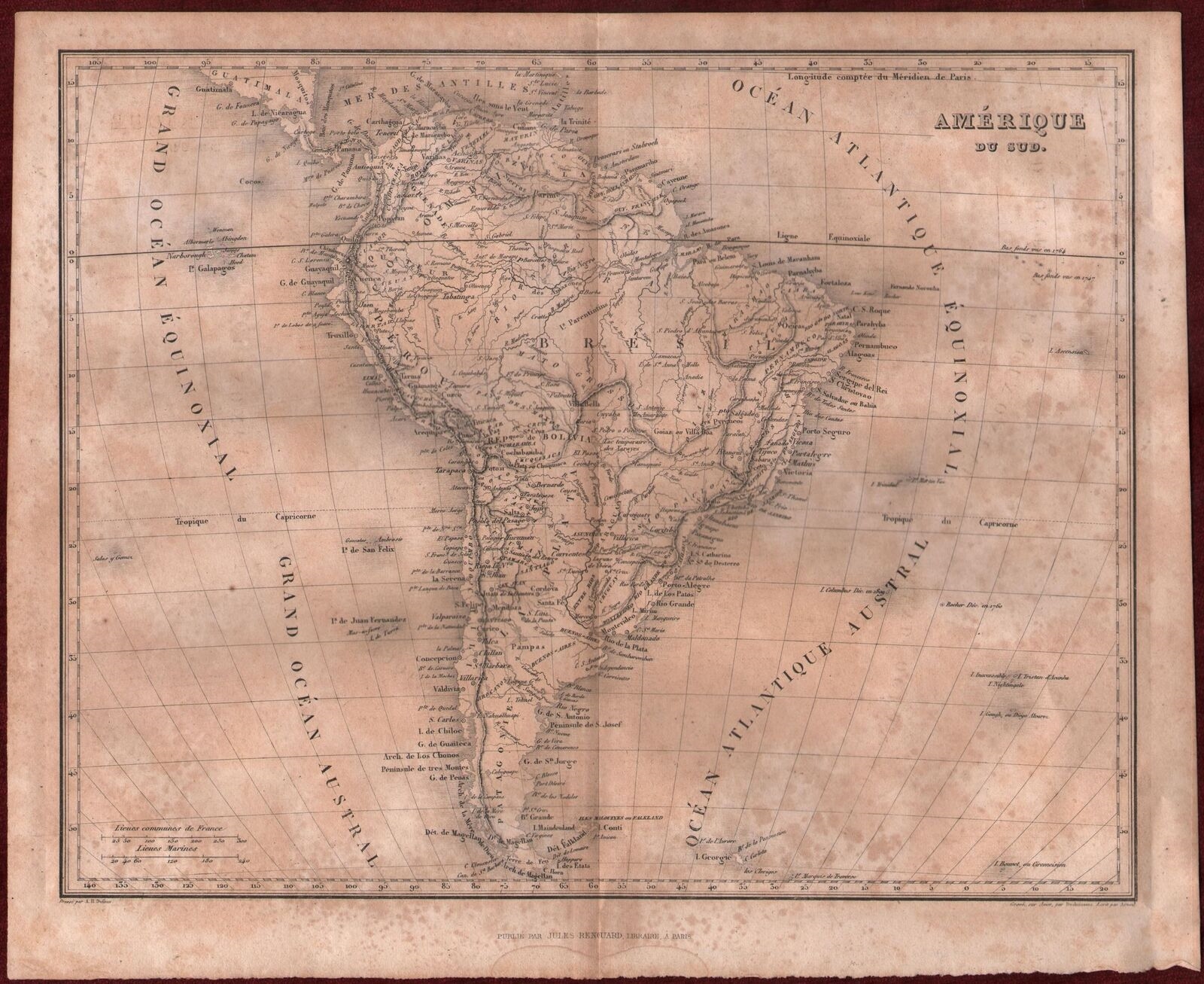

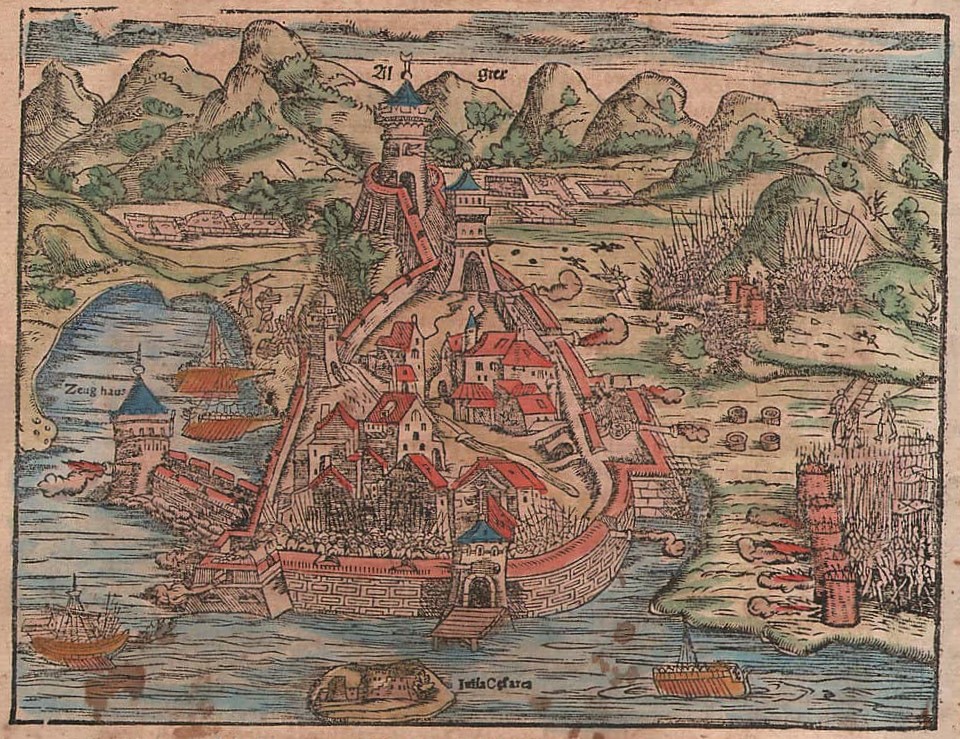

Jules Renouard greatly contributed to French cartography. He printed numerous maps of Europe, Africa, and America. In 1847, along with several colleagues, he founded the Cercle de la Librairie (The Bookstores Circle). It was actually a trade union of booksellers. Its head office was located at Saint German boulevard in Paris. The building itself still exists as a historical point of interest.

Father’s Legacy

We could say that being A.A. Renouard’s son came with privileges, which Jules did not take for granted. Antoine-Augustin, alongside bookselling, was a political activist and revolutionary. This finally led him to become the mayor of the 11th arrondissement of Paris and be rewarded with the Legion of Honour after the 1830 revolution.

While Jules’ good connections and marriage ties granted him status and influence, he followed in his father’s footsteps as an activist. The changes he pushed for weren’t political in essence, but a fight for cultural values and preservation of arts in the face of uprising plagiarism.

Plagiarism, Piracy & Copyrights

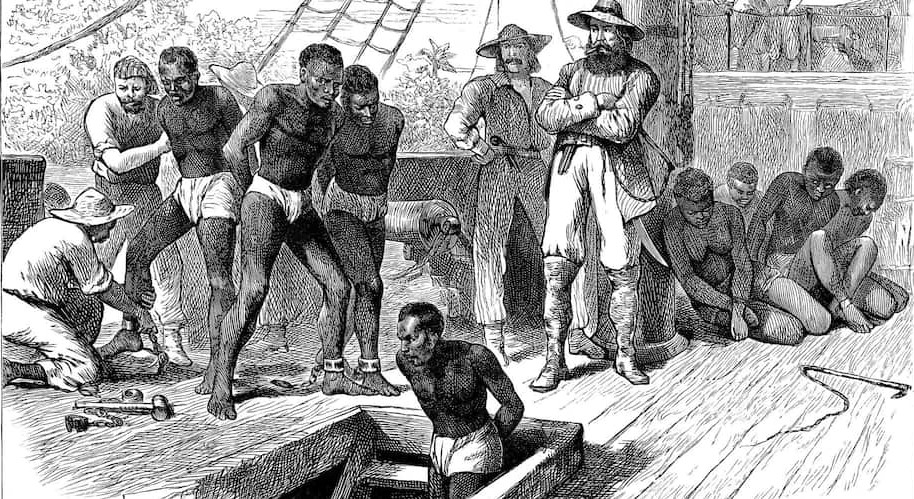

In 1851, Renouard delivered an important paper to the association under the title Progrès de la contrefaçon, dénonciation et protestation. The Progress of counterfeiting, denunciation, and protest protested against the unfair trading practices of foreign competitors. This was, in fact, an early fight against piracy, an important step for copyrights and the rights of the author. During his time, Jules Renouard tried his best to preserve French publishing houses and protect Parisian booksellers.

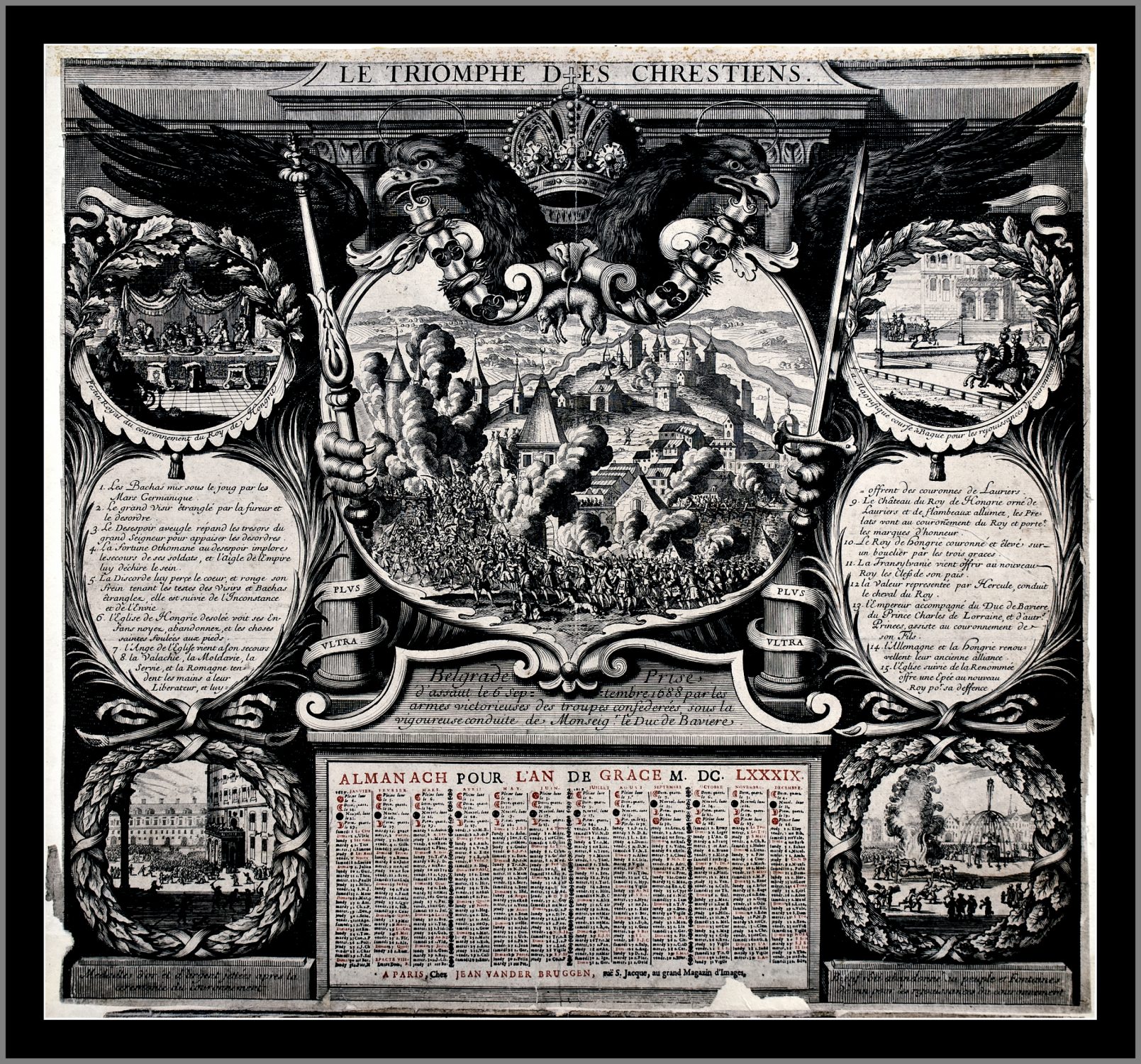

Aside from the literary rights, he also vouched for copyrights in art, giving an example of French engravings copied and sold in Germany at the time. Maybe hesitant to be called out as being financially motivated, his argument was aimed at the aesthetic quality of the reproductions. Not only they were cheap, but cheaply made, mocking thus the refined skill of great artists:

It will therefore be necessary for one Claude Lorrain, one Rubens and so many brilliant stars of color to groan under the muddy roll of these executioners of art!

What Remains

Nevertheless, as he wasn’t an artist himself, his interest was predominantly that of protecting the rights of publishers. And while his arguments alone didn’t withstand the test of time, they were certainly a step in the right direction. Namely, that of copyrights. Still, his essays bear no relevance in today’s discussions. What remains are the institutions he helped prop up along with a plethora of maps he published – a testimony to the quality of production he fought for.