1901 Aus Bismarcks Briefwechsel Bismarck Correspondence Germany Prussia William

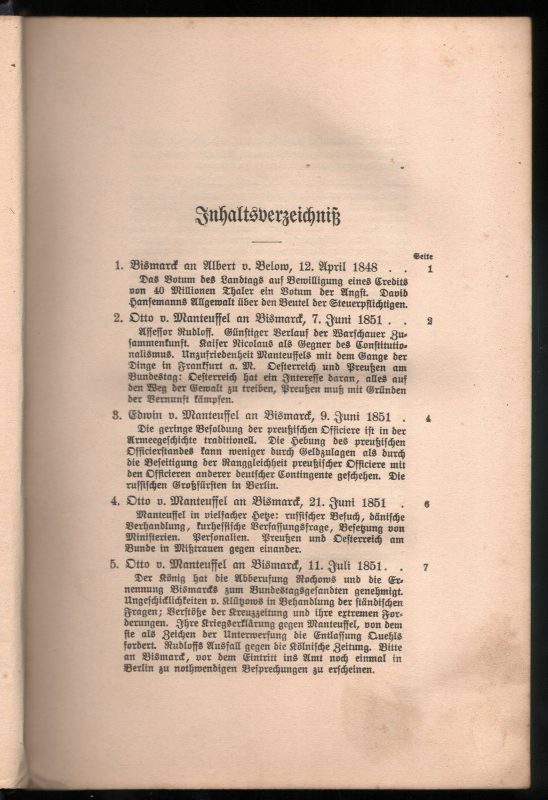

Aus Bismarcks Briefwechsel By Otto von Bismarck (Correspondences of Bismarck) – In German language.

***

Book contains Bismarck’s written correspondences from the period of German emperor William I. Second book from the series „Anhang zu den Gedanken und Erinnerungen“(Annex of the thoughts and memories).

***

Stuttgart and Berlin, J.G. Cotta’sche Buchhandlung Nachfolger, 1901.

***

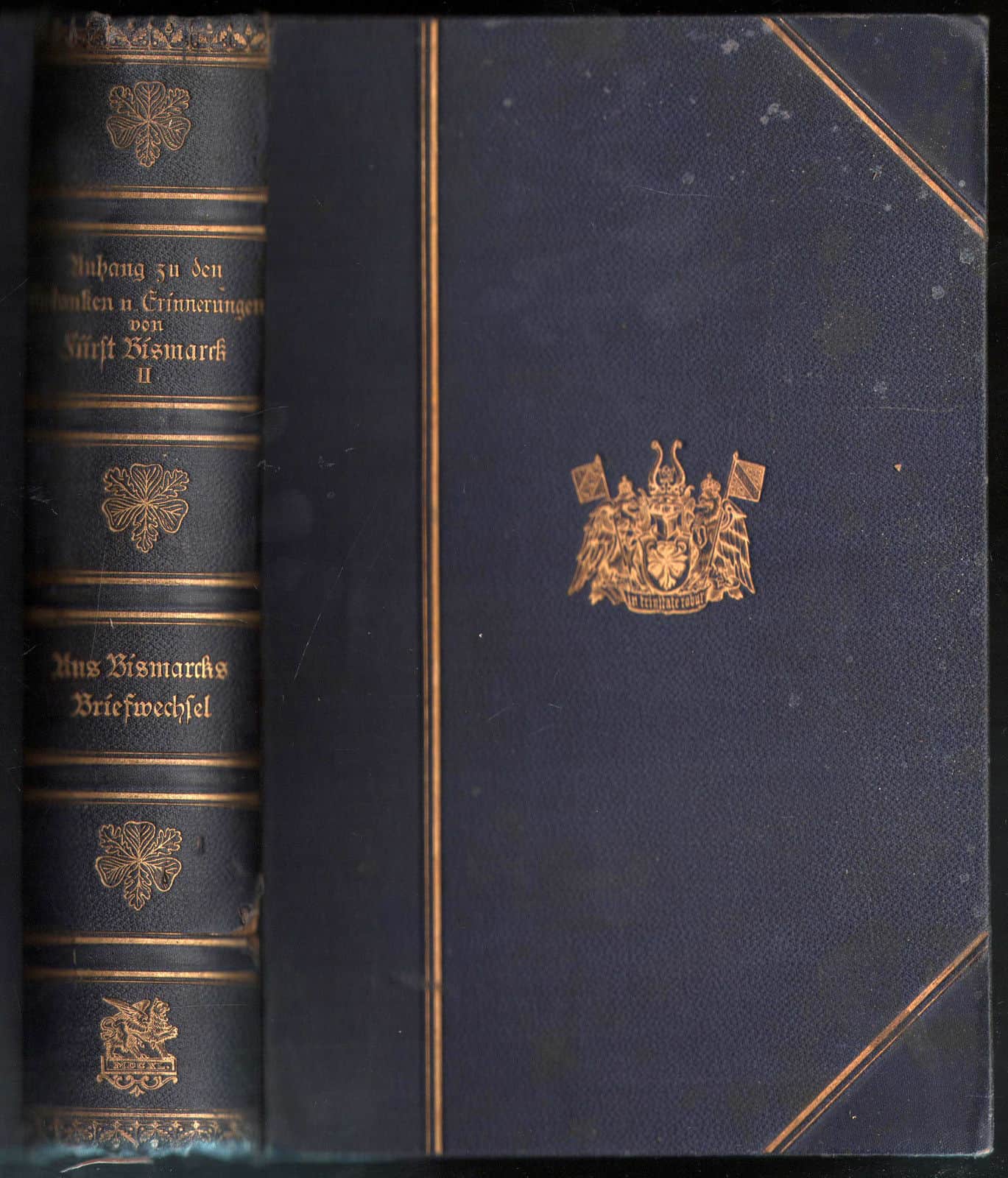

Pp.: [XLVI] + 567 Size: 23,5 x 16,5 cm

***

Binding: Original cloth leather binding. Giltstamped, stained, signs of wear on the panels and along the edges, cocked spine with spine slants, spine cover slightly damaged. Condition: Dated ink inscription on the flyleaf (14.6.1906). Stains on first and last few pages (foxing), clean copy otherwise.

***

For condition and details see the scans. For any additional questions feel free to contact us, we are eager to respond to all of your questions!

***

Otto Eduard Leopold, Prince of Bismarck, Duke of Lauenburg (1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), known as Otto von Bismarck, was a conservative Prussian statesman who dominated German and European affairs from the 1860s until 1890. In the 1860s he engineered a series of wars that unified the German states, significantly and deliberately excluding Austria, into a powerful German Empire under Prussian leadership. With that accomplished by 1871 he skillfully used balance of power diplomacy to preserve German hegemony in a Europe which, despite many disputes and war scares, remained at peace. For historian Eric Hobsbawm, it was Bismarck who “remained undisputed world champion at the game of multilateral diplomatic chess for almost twenty years after 1871, devoted himself exclusively, and successfully, to maintaining peace between the powers.” In 1862, King Wilhelm I appointed Bismarck as Minister President of Prussia, a position he would hold until 1890 (except for a short break in 1873). He provoked three short, decisive wars against Denmark, Austria, and France, aligning the smaller German states behind Prussia in its defeat of France. In 1871 he formed the German Empire with himself as Chancellor, while retaining control of Prussia. His diplomacy of realpolitik and powerful rule at home gained him the nickname the “Iron Chancellor.” German unification and its rapid economic growth was the foundation to his foreign policy. He disliked colonialism but reluctantly built an overseas empire when it was demanded by both elite and mass opinion. Juggling a very complex interlocking series of conferences, negotiations and alliances, he used his diplomatic skills to maintain Germany’s position and used the balance of power to keep Europe at peace in the 1870s and 1880s. A master of complex politics at home, Bismarck created the first welfare state in the modern world, with the goal of gaining working class support that might otherwise go to his Socialist enemies.[3] In the 1870s he allied himself with the Liberals (who were low-tariff and anti-Catholic) and fought the Catholic Church in what was called the Kulturkampf (“culture struggle”). He lost that battle as the Catholics responded by forming a powerful Centre party and using universal male suffrage to gain a bloc of seats. Bismarck then reversed himself, ended the Kulturkampf, broke with the Liberals, imposed protective tariffs, and formed a political alliance with the Centre Party to fight the Socialists. A devout Lutheran, he was loyal to his king, who argued with Bismarck but in the end supported him against the advice of his wife and his heir. While the Reichstag, Germany’s parliament, was elected by universal male suffrage, it did not have much control of government policy; Bismarck distrusted democracy and ruled through a strong, well-trained bureaucracy with power in the hands of a traditional Junker elite that consisted of the landed nobility. Under Wilhelm I, Bismarck largely controlled domestic and foreign affairs, until he was removed by the young Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1890, at the age of seventy-five. Bismarck—a Junker himself—was strong-willed, outspoken and sometimes judged overbearing, but he could also be polite, charming and witty. Occasionally he displayed a violent temper, and he kept his power by melodramatically threatening resignation time and again, which cowed Wilhelm I. He possessed not only a long-term national and international vision but also the short-term ability to juggle complex developments. As the leader of what historians call “revolutionary conservatism,”[4] Bismarck became a hero to German nationalists; they built many monuments honoring the founder of the new Reich. Many historians praise him as a visionary who was instrumental in uniting Germany and, once that had been accomplished, kept the peace in Europe through adroit diplomacy.