Blog

Giovanni Battista Piranesi: Master Printmaker of the 18th Century

Early Life and Training

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, celebrated as one of the greatest printmakers of the 18th century, always saw himself first as an architect. A son of a stonemason and master builder, Piranesi received practical structural and hydraulic engineering training from his uncle, who worked for the Venetian waterworks. His brother, a Carthusian monk, ignited his passion for ancient Roman history and achievements. Additionally, Piranesi’s education included in-depth perspective construction and stage design studies. Despite limited success in securing architectural commissions, this diverse training would prove invaluable in his printmaking career.

Journey to Rome and Mastery of Etching

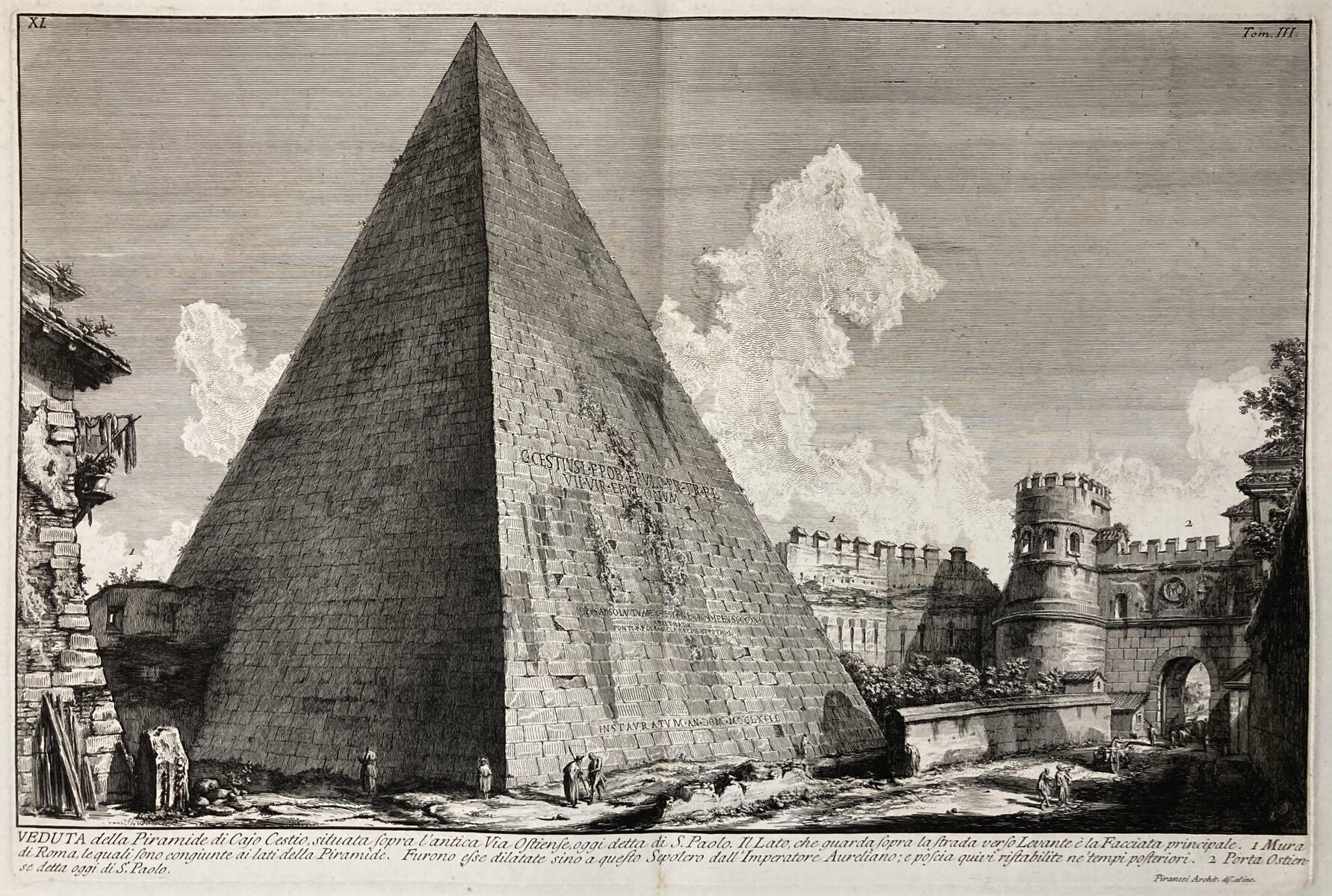

Shortly after arriving in Rome in 1740, Piranesi apprenticed with Giuseppe Vasi, a leading producer of etched views (vedutas) of the city.

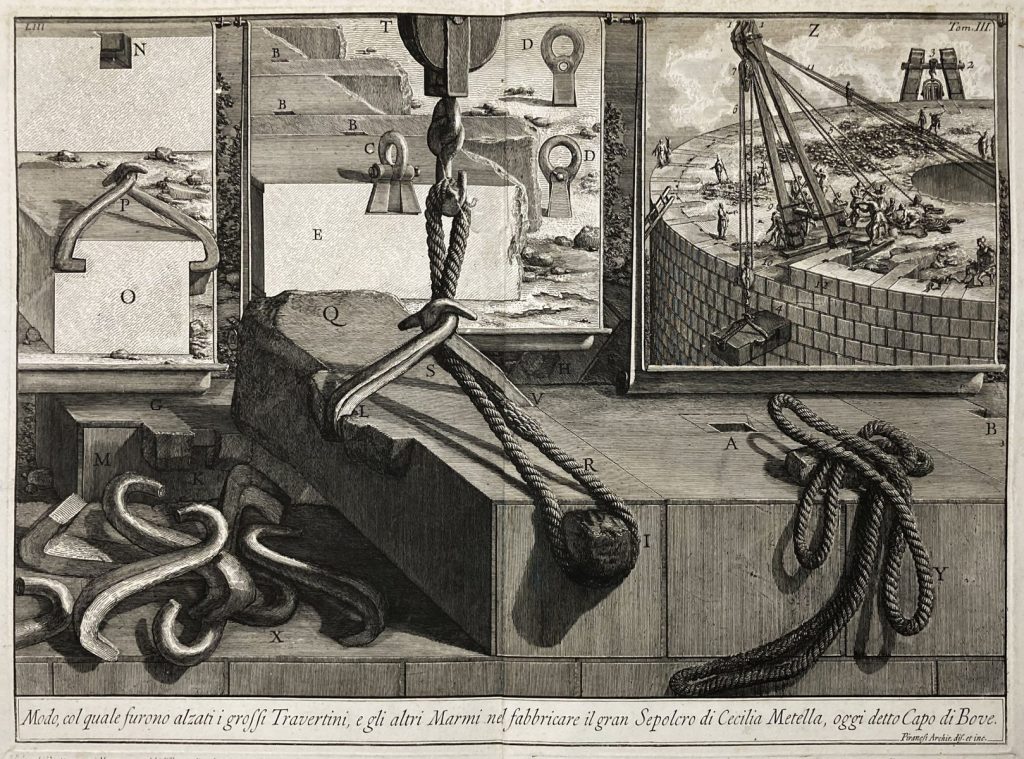

The tomb of Caecillia Metella located just outside of Rome, is masterfully shown in Piranesi’s etching.

He quickly mastered etching, which allowed him to channel his varied interests. His works ranged from fantastical architectural designs to meticulous reconstructions of ancient Roman aqueducts. Piranesi’s archaeological prints showcased his deep knowledge of ancient building techniques, earning him recognition as an antiquarian. His acclaimed “Antichità Romane” (1756) led to his election to the Society of Antiquarians of London. Etching also provided Piranesi with a steady income, as he drew both ancient and contemporary buildings of Rome.

The Vedute di Roma and Lasting Impact

By 1747, Piranesi embarked on his most famous work, the “Vedute di Roma” (Views of Rome), a series he continued until he died in 1778. These prints, known for their dynamic compositions and dramatic lighting, profoundly shaped European perceptions of Rome. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, familiar with Rome through Piranesi’s prints, felt a sense of anticlimax upon seeing the real city. Piranesi’s willingness to embrace printmaking was influenced by his ties to Venice, where many top artists of the time engaged in etching. His visits to Venice in the mid-1740s exposed him to the works of Canaletto and Tiepolo, inspiring his innovative series such as the “Grotteschi” and the “Carceri.”

Advocacy for Roman Art

Piranesi’s love for Rome and his contentious nature led him to join the mid-century debate on Greek versus Roman art. In his 1761 work “Delle magnificenza ed architettura de’ Romani,” he argued that the Romans learned from the Etruscans, not the Greeks, using his expertise in ancient engineering to highlight Roman creativity. Piranesi celebrated Roman ornamentation’s richness and variety, supporting his arguments through detailed etchings.

Piranesi, Giovanni Battista. Egyptian mural decoration for the Caffè degli Inglesi, Piazza di Spagna, Rome, 1769

While Piranesi championed Roman art, he appreciated Greek and Egyptian styles. His design for an Egyptian fireplace and the decorative scheme for the Caffè degli Inglesi in Piazza di Spagna exemplify his eclectic taste. In his 1769 preface to “Diverse maniere d’adornare i cammini,” Piranesi advocated for the freedom to draw inspiration from various styles. His etchings of mantelpieces and furniture influenced European decorative trends and served as a sales catalog for objects crafted from ancient remains. Piranesi even directed the execution of some designs, incorporating antique fragments from recent excavations.

Major Architectural Projects

Piranesi’s grandest architectural opportunities came during the reign of Venetian Pope Clement XIII (1758–69). Cardinal Rezzonico, the pope’s nephew, commissioned him for two major projects. Although his ambitious designs for the Lateran Basilica’s apse were never realized, Piranesi successfully renovated Santa Maria del Priorato, the church of the Knights of Malta on the Aventine Hill. His work included an impressive ceremonial piazza adorned with obelisks and trophies.

Legacy and Final Days

Piranesi once said: “I need to produce great ideas, and I believe that if I were commissioned to design a new universe, I would be mad enough to undertake it.” From these words, we can pretty much sum up how far his ambition and dedication went. The commitment to his work and his identification with Rome’s grandeur remained unwavering until his death. On his final day, he refused to rest, stating that repose was unworthy of a Roman citizen. He spent his last hours engrossed in his drawings and copperplates, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inspire and captivate.

Feel free to check out our collection of Piranesi’s prints.

Thanks for reading!